No Refuge in Mississippi – America Fails Yet Another Immigrant Woman

One of those mothers is my client, E.J. (she has given me permission to share her story, but I refrain from using her full name out of respect for her privacy and fear of retribution from ICE). E.J. is an indigenous Guatemalan woman of Mayan Mam descent who arrived in Mississippi nearly 10 years ago when she was just shy of her 20th birthday.

Like so many other indigenous Guatemalan women, she came to America to escape a system in which the indigenous population is marginalized and exploited and where violence against native women is so prevalent and widely accepted that the police do not even bother to fill out paperwork when reports of sexual assault are made by traumatized victims.

The day I met E.J. in a Louisiana ICE detention facility filled with hundreds of women from around the world, I asked her to tell me about her life as a Mayan Mam girl in Guatemala. The conversation was flowing smoothly as I spoke to E.J. through an interpreter, a student at Ole Miss Law, but my interpreter suddenly fell silent. E.J. continued to speak in a quivering voice hushed by emotion. Eager to know what had caused E.J.’s eyes to water and face to contort in emotion, I quickly turned to my student to see why she had fallen so far behind in bridging the linguistic gap caused by the ambivalence with which I approached foreign language study as a student.

My translator had fallen behind because E.J’s story had left her overwrought with emotion and unable to utter a word. Tears streamed down my Latina student’s face, and the fresh blue ink on her yellow legal pad created smudge puddles under the deluge of the salty droplets. We were suspended in that silence as E.J. and my student were struck mute by the horribleness of E.J.’s truth. I awkwardly shifted in my seat knowing that I, too, would soon know something terrible. But I dared not sever the connection between E.J. and my student fused by E.J.’s pain and my student’s empathy. I joined them in the lengthy silence as an uninformed tear rolled down my cheek.

E.J. was raped by 10 Guatemalan gang members when she was 16-years-old. After yet another afternoon of trudging door-to-door in her small town begging for food and enduring the ridicule of those who would sneer “here comes the indigenous begging for the scraps from our table,” E.J. noticed the group of men closing in from behind with bandanas covering their faces. She screamed for help, but the cries of Mayan women fall on deaf ears in E.J.’s hometown. The men dragged her into an alley and violently descended upon her. My student faltered again as she conveyed E.J.’s recollection of lying on the dirty street praying that God would let her die.

Nine months later, E.J. gave birth to her first child. E.J.’s mother kept E.J. and her daughter locked in the house knowing that the gang members who attacked E.J. always were nearby and that the same police who had refused to investigate when E.J. and her mother went to them on the evening of the attack would provide no protection – not without payments that E.J.’s family could never afford. The little freedom E. J. ever had was lost.

Nearly four years later, E.J. made the gut-wrenching decision to leave her daughter behind and set out for America in hopes of salvaging some kind of life for herself and her family back home. With the assistance of a “coyote” who got her across the border in exchange for every penny E.J.’s family could scrape together, E.J. made it to the Promised Land. She made her way to Mississippi where hundreds of other indigenous Guatemalan refugees had found work killing, butchering, and packaging chickens in abhorrent conditions for barely more than minimum wage.

E.J. did that filthy work for eight years. Along the way, she met a kind indigenous Guatemalan man who loves her and wants to marry her someday. They have been together for six years, and they have a four-year-old son who has a language disorder and is enrolled in special education in the local schools. E.J. was living that sliver of the American Dream reserved for the vulnerable and marginalized.

On the morning of August 7, 2019, E.J. was rounded up with hundreds of her co-workers, restrained with zip ties, and hauled off to a hangar at the nearby Mississippi National Guard facility where ICE agents were herding detainees through a lengthy intake process. Despite explaining how her American-born son desperately needed her and begging to be allowed to return to him, E.J was whisked away to a private prison in Louisiana being paid millions each month by the American government to warehouse people caught in ICE’s net. E.J.’s freedom, if she ever really had any, was lost.

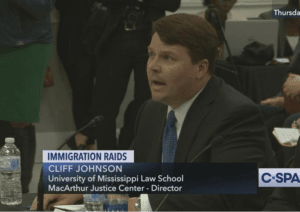

I filed my first-ever immigration pleadings and participated in my first-ever immigration hearings on E.J.’s behalf. The American government wants to send her back to the same small town in Guatemala where she was violated 14 years ago.

Fueled by anger and indignation and equipped with zero experience and shockingly little substantive knowledge, I found myself engaged in truncated proceedings conducted via video camera by a judge sitting thousands of miles from Louisiana.

On March 4, 2020, nearly seven months after being hauled away as part of a now-forgotten political farce, E.J. walked out of that Louisiana detention center and held her son for the first time in 210 days. They snuggled together in the backseat as her partner drove the six hours back to their home in Mississippi.

E.J. has returned to life as an undocumented immigrant in Mississippi. She takes care of her son and hopes to return to the cutting line at the local chicken plant if we can convince ICE to give her permission to work while she awaits the ultimate resolution of her immigration case. E.J. won’t have her final court date for another two or three years thanks to the million-case backlog in United States immigration courts. Whenever that day comes, we’ll be there beside her fighting for her freedom – to the extent she can ever really have any.

Takeaways

-

Only 2% of Mississippi’s population

was born in another country, but the two largest ICE raids in American history have occurred there. -

The fact that Mississippi has only a handful of immigration lawyers,

a U.S. Attorney eager to support ICE, and United States Senators who are staunch supporters of President Trump creates an environment conducive to mass enforcement efforts by ICE. -

Felony charges

have been brought against more than 125 people detained in last year’s raids by U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Mississippi. Previous ICE raids resulted in very few criminal prosecutions. -

The stakes are incredibly high

when it comes to bond in immigration proceedings. Those who remain in ICE detention facilities face final removal proceedings within months. -

Detainees released on bond

likely will won’t face an ultimate removal proceeding for two to three years (long enough for a change in American immigration policy depending on the outcome of November’s election). -

The MacArthur Justice Center

in Mississippi has been instrumental in raising more than $900,000 to pay bonds for almost 100 people detained in last year’s raids.