Today is International Wrongful Conviction Day. #WrongfulConvictionDay

A wrongful conviction is no longer a shock – it’s a well-known fact of our criminal justice system. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, there have been 2,499 exonerations in the U.S. since 1989.

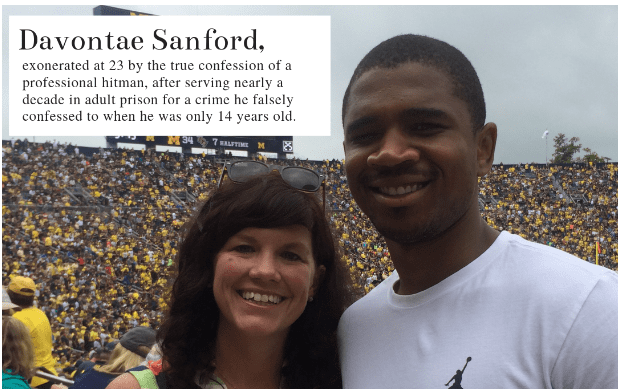

While it is certainly depressing that so many people have been wrongfully convicted in our country – a former 9th Circuit judge estimated the actual wrongful conviction rate is at least two times higher than the current statistics – the increasing rate of exoneration is historic and encouraging. Media has played a critical role in exposing these injustices. Take Brendan Dassey, the 16-year-old made famous by Netflix’s Making a Murderer who falsely confessed to rape and murder; his story likely would have remained unknown if not for two intrepid filmmakers. #bringbrendanhome. Or Davontae Sanford, whose exoneration after growing up behind bars from ages 14-23 would not have been possible if not for a reporter exposing the fact that a professional hitman had confessed to the crime for which Sanford was doing the time. Thanks to popular culture’s embrace of these stories, the public understands that wrongful convictions happen and that our system is far from perfect.

What the public knows less about is what happens after a wrongfully convicted person is released from prison. What happens after the first taste of freedom wears off, when the supporters and media attention fades? How does a person rebuild a life – or for many people who went into prison as youth – build a life for the first time? Not to mention the trauma of being innocent in prison that they bring home.

The recent Netflix miniseries When They See Us by Ava DuVernay about The Exonerated Five, formerly known as The Central Park Five, gave us a glimpse into this reality. Without an education, an employment history, or a stable home, one of the Five resorted to selling drugs and was back in prison months after his release. While tragic, it’s unfortunately not surprising.

The sad truth is that exonerees actually face more challenges post-release than those who committed a crime, served a sentence, and were released on parole. It’s counter-intuitive but true; state parole systems include a variety of reentry programs for parolees, such as housing and job training, that are not available to exonerees (simply because they are not technically “on parole”). I know of only one exoneree-focused organization, After Innocence, based in California, which has stated that “the vast majority of exonerees . . . never receive any consistent, reliable help with rebuilding their lives.”

the vast majority of exonerates…never receive any consistent, reliable help with rebuilding their lives.

After Innocence

Some states offer compensation for years spent wrongfully convicted, but shockingly, 15 states offer nothing at all. Even in states where it is available, the amount of compensation falls far below even minimum wage. In Missouri, where I practice, an exoneree is only eligible for compensation if DNA proved their innocence, which effectively rules out many of modern exonerations.

So what can an exoneree do to sustain their new freedom? One of the most potent tools at their disposal is to file a civil rights lawsuit. That’s the work we do at the MacArthur Justice Center.

The obvious tangible benefit is financial – the exoneree finally has the resources to build a life and move on with their story. Many exonerees pay the financial benefit forward. Take Korey Wise, who donated millions to fund the Innocence Project in Colorado at Colorado Law School. Other regional innocence projects are partially funded by the attorneys’ fees that result from successful civil litigation.

A civil lawsuit is also an exoneree’s opportunity to hold those responsible accountable. While wrongful convictions are all too common, it is all too rare for those responsible to admit any culpability – let alone implement necessary reforms. In the medical world, after a preventable death, hospitals conduct a sentinel review. There is no comparison in the criminal justice world – but there should be. Until then, the primary tool for accountability – and for hopefully preventing similar misconduct and more wrongful convictions in the future – we have is force key actors to pay up.

A civil rights lawsuit provides one of the only moments when an exoneree may receive an acknowledgment of wrongdoing, if not an apology. Even more, it forces the State to pay attention. While payouts for exonerees sometimes get a bad rap because taxpayer dollars are spent, this money is essential to holding people accountable and creating real change. I’d love to believe our client’s story of injustice is enough, the truth is change happens more often when it impacts the government’s bottom line.

But a disturbing trend is afoot with prosecutors; some are offering the wrongfully convicted deals that condition their release on an agreement not to sue. This makes me furious. It makes Larry Krasner, Philadelphia’s progressive district attorney, furious too: “Simply put, I think the whole thing is despicable.” You should be furious as well.

Simply put, I think the whole thing is despicable.

Larry Krasner

Exonerees are amazingly resilient, and somehow often not angry. My exonerated clients have been determined to move forward, and not allow their wrongful conviction to control one more day of their life than it already has. Nonetheless, they are hungry for the wrong done to them to be acknowledged, for their injustice and suffering to be recognized, and for someone to be held accountable. While the damage cannot be undone, a court order, one that holds the bad actors responsible and forces financial accountability, allows healing to truly begin.

Takeaways

-

2,499

exonerations in the U.S. since 1989 -

15

states do not offer any compensation for years spent wrongfully convicted