Accountability at the Court Part 1: Bivens Actions & Fields

One of the most important tools for holding officials accountable is a suit for monetary damages. Damages allow courts to compensate (to the extent possible) a person for harm they have suffered, and to deter future violations by imposing financial costs on the wrongdoers. As the Supreme Court recently noted, “[i]n the context of suits against Government officials, damages have long been awarded as appropriate relief,” dating back to the earliest days of the Republic. Tanzin v. Tanvir, 592 U.S. 43, 49 (2020).

Indeed, damages are often “the only form of relief” available. Id. Courts cannot, for example, issue an injunction (discussed more in Part 3) when a violation—such as an assault, the destruction of property, or wrongful detention—has already occurred, unless it can be shown that the same violation is likely to recur. One of the Supreme Court’s most famous cases on injunctive relief—City of Los Angeles v. Lyons—held that a man whom Los Angeles police officers unlawfully put in a chokehold, rendering him unconscious and damaging his larynx, could not seek an injunction. The Court concluded that he did not even have standing to request an injunction because he could not allege that the same thing was likely to happen to him again. See City of Los Angeles v. Lyons, 461 U.S. 95, 105-06 (1983). In doing so, the Supreme Court took comfort in the fact that “[t]he legality of the violence to which Lyons claims he was once subjected is at issue in his suit for damages and can be determined there,” underscoring the importance of damages actions. Id. at 111.

For city officials, like the police officers in Lyons, and state officials, the mechanism for bringing a lawsuit seeking monetary damages was established by the Civil Rights Act of 1871, also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, or simply Section 1983. That statute provides that “[e]very person” who violates a citizen’s federal legal rights while acting “under color” of state law “shall be liable” in an action seeking damages, an injunction, or other proper relief. 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Section 1983 provides the legal vehicle—or “cause of action”—that allowed the plaintiff in Lyons, Mr. Adolph Lyons, to sue the officers and seek damages. See Lyons v. City of Los Angeles, 656 F.2d 417, 417 (9th Cir. 1981). And it continues to be the foundation of civil rights lawsuits across the country today, including suits about police shootings, solitary confinement, false arrest, and malicious prosecution.

Congress never enacted a comparable statute for federal officials. Instead, the mechanism for bringing a lawsuit seeking monetary damages against federal officials arises from a Supreme Court decision called Bivens. In 1971, the Supreme Court recognized what seemed like an obvious principle at the time: Federal officials, as much as state officials, must be held accountable when they violate people’s rights. In that case, six agents of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics—the predecessor to the Drug Enforcement Administration—stormed into the apartment of a person named Webster Bivens, manacled him “in front of his wife and children,” and “threatened to arrest the entire family.” Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of Federal Bureau of Narcotics, 403 U.S. 388, 389 (1971). The agents searched the apartment “from stem to stern,” and then hauled Mr. Bivens out of his home, taking him to the Brooklyn federal courthouse, where he was subjected to a strip search. Id. Mr. Bivens sued the agents—seeking $15,000 in damages from each—for invading his home without a warrant, using excessive force against him, and arresting him without probable cause to believe he had committed any crime. In response, the agents attempted to argue that, regardless of whether they had violated Mr. Bivens’ rights, Mr. Bivens had no cause of action to bring a suit for damages against them. The Supreme Court roundly rebuffed the argument, declaring that “where federally protected rights have been invaded, it has been the rule from the beginning that courts will be alert to adjust their remedies so as to grant the necessary relief.” Id. at 392. That federal agents could be sued for damages for violating the Constitution, the Court added, “should hardly seem a surprising proposition.” Id. at 395.

In the decades since Bivens, the Supreme Court has become much less alert to redressing violations by federal officials. Instead, the Supreme Court has repeatedly refused to permit ordinary people from using Bivens to sue federal officials. For example, about a decade after Bivens, in Chappell v. Wallace, 462 U.S. 296 (1983), several Navy sailors sued their commanding officers for discriminating against them on the basis of race. Id. at 297. The Supreme Court refused to allow that suit, reasoning that Congress, as “the constitutionally authorized source of authority over the military system of justice,” had not enacted a statute authorizing such a suit, and federal courts should be reluctant to interfere in “[t]he special nature of military life” by permitting a “judicially created remedy.” Id. at 304. As a result, to this day, “enlisted military personnel may not maintain a suit to recover damages from a superior officer for alleged constitutional violations.” Id. at 305. Similarly, a few years later, when an Army master sergeant sued the Army for secretly testing the effects of LSD on him during a study ostensibly designed to evaluate protective clothing against chemical warfare, the Supreme Court made clear that there is simply “no Bivens remedy” available “for injuries that arise out of or are in the course of activity incident to service.” U.S. v. Stanley, 483 U.S. 669, 684 (1987). No damages; no accountability.

The Court has given the same treatment to private prison companies employed by the federal government. See Correctional Services Corp. v. Malesko, 534 U.S. 61 (2001); Minneci v. Pollard, 565 U.S. 118 (2012). So too for federal medical personnel responsible for providing care to those in ICE detention. See Hui v. Castaneda, 559 U.S. 799 (2010). And so too for Border Patrol agents who shot and killed an unarmed fifteen-year-old child and violently arrested another person. See Hernandez v. Mesa, 589 U.S. 93 (2020); Egbert v. Boule, 596 U.S. 482 (2022). In all of these cases, the Court held that, regardless of whether federal officials violated people’s rights and caused them harm, there was no cause of action available to seek damages for those wrongs.

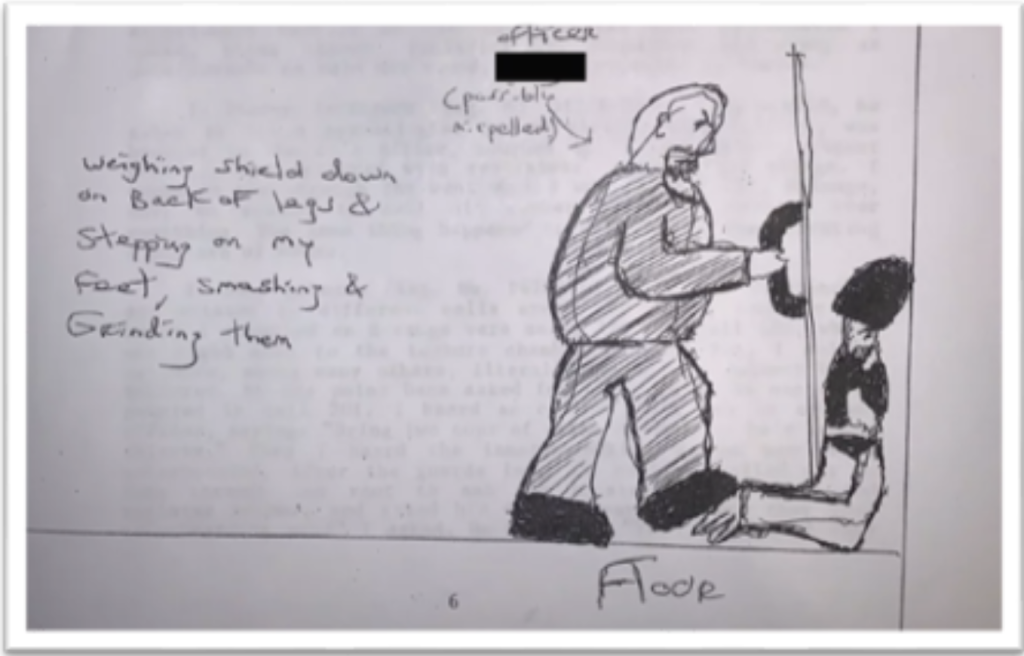

That brings us to this past term, when the Court addressed another important category of federal officials: guards employed by the Federal Bureau of Prisons. In Fields v. Goldey, 606 U.S. 942 (2025), the Court summarily reversed—without even receiving merits briefing or hearing oral argument—a decision by the Fourth Circuit permitting a person from suing federal officials at the U.S. Penitentiary in Lee County, Virginia, for a series of vicious assaults. The rampant abuse at USP-Lee has been widely reported on, as dozens of people have described “a culture of violence,” including punitive uses of four-point restraint boards and ruthless beatings with shields, boots, and fists, as depicted below:

Mr. Andrew Fields described the same kind of abuse in a lawsuit he filed in 2022. As he lay shackled in an observation cell, officials took turns assaulting him, “including by ramming his head into the concrete wall and hitting [him] with a fiberglass security shield.” Fields v. Federal Bureau of Prisons, 109 F.4th 264, 268 (4th Cir. 2024). He sued for damages, and the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals held that this “egregious physical abuse with no imaginable penological benefit” should be evaluated through a Bivens action. Id. at 272. The Court emphasized that, as the government itself conceded, Mr. Fields’ case was “rare” and extreme, making it especially deserving of a judicial remedy. Id.

The Supreme Court, however, stopped Mr. Fields’ suit in its tracks. In a short, unsigned opinion, the Court held that Mr. Fields’ allegations—no matter how meritorious—cannot be brought in federal court to seek damages against federal officials. The Court’s reasoning followed a familiar pattern. First, it concluded that Mr. Fields’ claim was different—“meaningfully different,” to be precise—from the Bivens actions that the Supreme Court has approved in the past. There are three such actions: the Fourth Amendment claims in Bivens, a Fifth Amendment claim in a case called Davis v. Passman, 442 U.S. 228 (1979), and an Eighth Amendment claim in a case called Carlson v. Green, 446 U.S. 14 (1980). Compared to the facts of those cases, the Court briskly concluded that “[t]his case arises in a new context.” Fields, 606 U.S. at 944.

Second, the Court refused to recognize the “new” Bivens context. Outside of cases mirroring the original three Bivens cases, the Supreme Court has instructed federal courts to ask whether it is appropriate to permit a cause of action for another kind of violation—i.e., to “extend Bivens.” Here, the Court concluded that there were “special factors” weighing against permitting Mr. Fields’ Bivens action to proceed. Congress, for example, has enacted laws relating to “prisoner litigation,” but has not expressly created a statutory cause of action like Section 1983. Id. Allowing such an action, the Court worried, “could have negative systemic consequences for prison officials and the ‘inordinately difficult undertaking’ of running a prison.” Id. (Presumably, those consequences would include being held responsible for egregious abuses of power. The Court seemed to assume that being able use violence without consequences makes the “difficult undertaking” of running a prison easier.)

The Court also pointed to the existence of “alternative remedial procedures,” referring to the Bureau of Prisons’ administrative grievance process, known as the Administrative Remedy Program. That complicated, four-step procedure can take months to complete, and often results in the denial of relief even when prisoners manage to jump through its many hoops. It also provides no opportunity for the award of damages, and the Supreme Court acknowledged that whatever relief is technically available may not be “as effective as an individual damages remedy.” Id. at 944-45. On top of it all, Mr. Fields had specifically alleged that federal officers “intentionally withheld” those very administrative remedies from him, preventing him from seeking any relief through that alternative system. Fields, 109 F.4th at 272.

Nevertheless, on these bases, the Supreme Court concluded that Mr. Fields had no Bivens remedy. “For the past 45 years,” the Court explained, “this Court has consistently declined to extend Bivens to new contexts. We do the same here.” Fields, 606 U.S. at 945 (citation omitted). Recognizing Bivens actions, the Court reiterated, is “disfavored judicial activity.” Id. at 944.

USP-Lee, the facility at which Mr. Fields was assaulted, is about 27 miles from a Virginia state corrections facility called Wallens Ridge State Prison. If Mr. Fields had been assaulted there, he would be able to bring a cause of action against the responsible officials under Section 1983. He would not have to prove that his exact claim had been approved before by the Supreme Court, and it would not matter whether allowing a damages action makes it more difficult to “run a prison.” But because federal officials, not state officials, administer USP-Lee, Mr. Fields’ suit was barred.

Looking ahead, a majority of the Court has stated openly that “if we were called to decide Bivens today, we would decline to discover any implied causes of action in the Constitution.” Egbert, 596 U.S. at 502 (emphasis added). Thus far, the Court has conspicuously avoided taking the ultimate step of overruling Bivens. Whether, and if so when, it does remains to be seen. Every time a federal court permits a Bivens claim to proceed creates another potential opportunity. See, e.g., Schwartz v. Miller, No. 23-1343, 2025 WL 2473008 (9th Cir. Aug. 28, 2025). Choosing to close the door completely on damages actions against federal officials in the era of President Trump, of all times, would be remarkable.