Accountability at the Court Part 2: FTCA Actions & Martin

One alternative to suing federal officials for their violations of federal rights is to sue the United States itself. Normally, a suit against the United States would be barred by federal sovereign immunity, but in 1946, Congress enacted the Federal Tort Claims Act, which created a limited waiver of federal sovereign immunity for certain claims. See 28 U.S.C. § 1346. That law permits district courts to hear “civil actions on claims against the United States, for money damages,” based on “the negligent or wrongful act or omission of any employee of the Government while acting within the scope of his office or employment,” if state law would make such a person liable in tort. Id. § 1346(b)(1).

Congress has long understood the FTCA and Bivens “as parallel, complementary causes of action.” Carlson, 446 U.S. at 20. In theory, therefore, a person harmed by federal agents should have both “an action under the FTCA against the United States as well as a Bivens action against the individual officials.” Id. (emphasis added). Indeed, while the FTCA ordinarily makes its remedies “exclusive of any other civil action or proceeding for money damages by reason of the same subject matter,” 28 U.S.C. § 2679(b)(1), the exclusive-remedies provision explicitly carves out claims based on “a violation of the Constitution of the United States,” id. § 2679(b)(2).

The FTCA contains a number of important limitations, however, on people’s ability to seek relief. First, the FTCA contains an exception for intentional torts: Suit under the FTCA is not permitted for “[a]ny claim arising out of assault, battery, false imprisonment, false arrest, malicious prosecution,” and several other intentional torts that commonly underlie abuses of power by federal officials. 28 U.S.C. § 2680(h). This is known as the “intentional-tort exception.” Second, suit under the FTCA is also not permitted for any claim “based upon the exercise or performance or the failure to exercise or perform a discretionary function or duty.” Id. § 2680(a). In other words, suit is not permitted if the challenged “function or duty” involves the “permissible exercise of policy judgment.” Berkovitz v. United States, 486 U.S. 531 (1988). This is known as the “discretionary-function exception.”

In a convoluted twist, the FTCA’s intentional-tort exception contains an exception: It does not apply—which is to say, suit is permitted—for “acts or omissions of investigative or law enforcement officers of the United States Government.” Id. § 2680(h). That caveat—known as the “law enforcement proviso”—applies not just to investigative misconduct, such as “executing a search, seizing evidence, or making an arrest,” but anything “within the scope” of a federal law enforcement officer’s employment. Millbrook v. United States, 569 U.S. 50, 56-57 (2013).

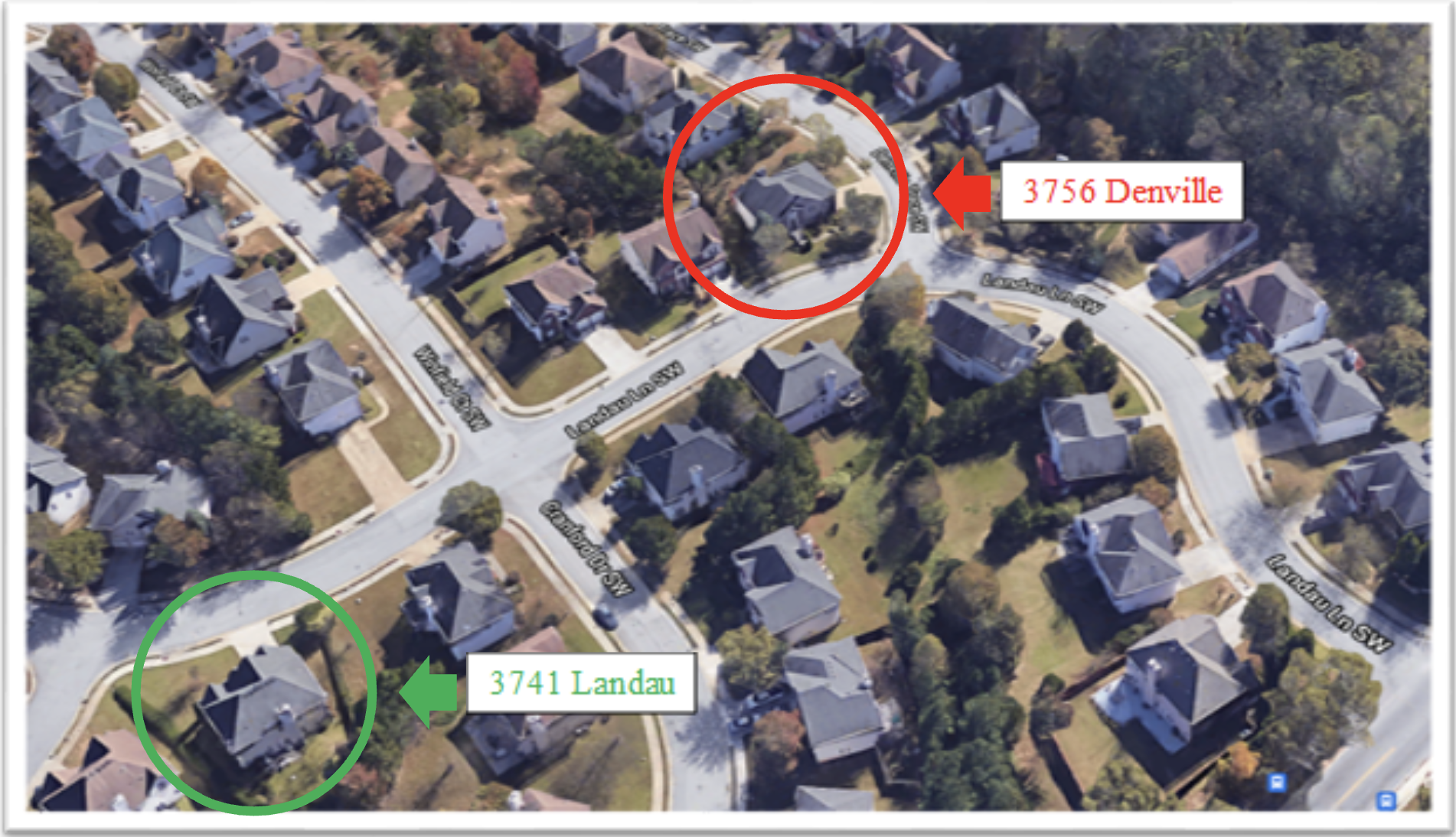

Both exceptions—the intentional-tort exception and the discretionary-function exception—were at issue in Martin v. United States, 145 S. Ct. 1689 (2025). That case concerned a stunning display of incompetence by federal officers, who “raid[ed] the wrong house, caus[ed] property damage and assault[ed] innocent occupants.” Id. at 1694. FBI agents intended to storm a suspected gang hideout at 3741 Landau Lane in suburban Atlanta. Id. In preparation, one agent visited that house to document its features and identify a staging area for the SWAT team. Id. That same agent was responsible for directing the SWAT team to the house on the day of the raid. Id. But using his personal GPS, the agent led the team to 3756 Denville Trace, about a block down the street. Id.

There were a number of clues that the agents were at the wrong house. The number “3756” was posted on the mailbox at the end of the driveway. Martin v. United States, 631 F. Supp. 3d 1281, 1288 (N.D. Ga. 2022). There was a different car in the driveway than the agent had recalled seeing during his site visit. Id. The warrant the agents were executing also included a “description and photograph of the home,” and “step-by-step directions to the property with a corresponding map.” Id. at 1287.

Despite these clues, none of the agents realized their mistake. Instead, they proceeded to raid the home, breaching the front door, detonating a flash-bang grenade, and storming inside with weapons drawn. Martin, 145 S. Ct. at 1694. The residents, Hilliard Cliatt, Curtrina Martin, and their 7-year-old son, hid in terror from what they believed was a home invasion. Id. Ms. Martin was half-naked at the time. Id. The officers dragged Mr. Cliatt out of the closet in which he was hiding, handcuffed him, and began “bombarding” him with questions. Id. Eventually, one officer found mail addressed to “3756 Denville Trace.” Id.

Mr. Cliatt, Ms. Martin, and their son sued the United States, the agent who directed the team to their house, and several other unnamed FBI agents, alleging claims under both Bivens and the FTCA. See Martin v. United States, No. 1:19-cv-4106 (N.D. Ga.), ECF 1 & 115. The district court rejected the Bivens claim, but not on the ground that there was no Bivens cause of action—perhaps because the facts of the case so closely resembled the facts of Bivens itself. Rather, the district court held that the named agent was entitled to qualified immunity. Martin, 631 F. Supp. 3d at 1295. In the court’s view, the agent’s actions were not “plainly incompetent” and he did not “knowingly violate the law” in light of the judicial precedent available at the time. Id. at 1294.

The district court also denied the FTCA claims. Its analysis proceeded in roughly three steps. First, it concluded that all of the named agent’s actions in executing the search warrant were “covered under the discretionary function exception,” which meant they could not be the basis for suit. Id. at 1297. Second, the court concluded that the claims based on false arrest, false imprisonment, and assault & battery were revived by the law enforcement proviso, since it was undisputed that the agent was a law enforcement officer. Id. at 1297. And finally, the court determined that those claims were nevertheless barred by the Supremacy Clause, based on a unique doctrine developed in the Eleventh Circuit. See Martin v. United States, No. 1:19-cv-4106, 2022 WL 18263039, at *3 (N.D. Ga. Dec. 30, 2022). On appeal, the Eleventh Circuit affirmed. See Martin v. United States, No. 23-10062, 2024 WL 1716235, at *8 (11th Cir. Apr. 22, 2024).

When the case reached the Supreme Court, it did two things, and failed to do a third. First, it held that the courts below had erred by assuming that the law enforcement proviso could revive claims barred by the discretionary function exception. Rather, the proviso “countermand[s] only § 2680(h)’s intentional-tort exception.” Martin, 145 S. Ct. at 1697. Accordingly, if a claim is barred by the intentional-tort exception, it may be revived by the law enforcement proviso; but if a claim is separately barred by the discretionary-function exception, the law enforcement proviso cannot save it. In other words, these exceptions provide independent pathways for a federal court to reject an FTCA claim, and the law enforcement proviso limits only one of them. In this way, the Court interpreted the FTCA to be restrictive in what claims it barred.

Second, the Court held that the Supremacy Clause does not provide an independent defense to FTCA claims. See id. at 1702. Accordingly, if a party has a viable claim under the FTCA, it does not need to overcome the additional defense developed by the Eleventh Circuit. In this way, the Court eliminated one hurdle to bringing an FTCA claim that the Eleventh Circuit had created.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the Court failed to determine whether any of the claims were barred by the discretionary-function exception. It acknowledged that whether a function is discretionary “is often less clear cut.” Id. at 1695. That is putting it lightly; lower courts throughout the country have “struggl[ed] to discern” how to apply the Supreme Court’s limited guidance on this vague and potentially broad exception. Id. Most recently, in a 34-year-old decision called United States v. Gaubert, 499 U.S. 315 (1991), the Court reiterated that the exception covers conduct involving “an element of judgment or choice” and which is “based on considerations of public policy.” Id. at 322-23.

Attempting to interpret guidance like this, “lower courts have taken different views of the discretionary-function exception,” creating multiple circuit splits. Martin, 145 S. Ct. at 1703. One such split, for example, turns on whether federal officials who violate the Constitution necessarily fall outside the exception because “[f]ederal officials do not possess discretion to violate constitutional rights.” Xi v. Haugen, 68 F.4th 824, 838 & n.10 (3d Cir. 2023). Nevertheless, in Martin, the Court failed to provide further guidance on the discretionary function exception, instead remanding for the Eleventh Circuit to consider. Martin, 145 S. Ct. at 1703.

As a federal circuit judge recently wrote, “the stakes of clarifying the scope of the discretionary-function exception” have grown especially high because of how Bivens has been “sharply limited.” Xi, 68 F.4th at 844 (Bibas, J., concurring). The Supreme Court’s refusal to permit suits against federal officials under Bivens, as discussed in Part 1, has elevated the role of the FTCA in redressing and deterring violations.

In light of the importance of the questions dividing the circuit courts, Justice Sotomayor expressly called for the Court’s review, stating that “it is long past time for this Court to weigh in on the exception’s scope.” Martin, 145 S. Ct. at 1705 (Sotomayor, J., concurring). Otherwise, lower courts may apply the discretionary-function exception too broadly. Indeed, as Justice Sotomayor explained, this kind of wrong-house raid was one of the main impetuses behind a major revision to the FTCA. See Martin, 145 S. Ct. at 1706. There is no reason to think that Congress intended to bar lawsuits concerning “liability in the very cases Congress amended the FTCA to remedy.” Id.

And yet, based on the limited guidance about the scope of the FTCA, the district court in Martin determined that the named agent’s actions “are covered under the discretionary function exception.” 631 F. Supp. 3d at 1297. The Eleventh Circuit similarly concluded that the exception “bars Appellants’ tort claims for trespass and interference with private property, negligent/intentional infliction of emotional distress, and negligence”—the claims that had not been “revived” in the district court’s analysis by the law enforcement proviso—because the agent “enjoyed discretion in how he prepared for the warrant execution,” and the “decision as to how to locate and identify the subject of an arrest warrant . . . is susceptible to policy analysis.” 2024 WL 1716235, at *7. Construed broadly enough, those terms might encompass nearly any decision, no matter how “unfortunate.” Id.

Whether, and how, the Court chooses to clarify the reach of the FTCA’s discretionary-function exception will have a major impact on one of the remaining tools for holding federal officials accountable.