A New Hope for Juveniles on Life Without Parole

In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court banned mandatory life sentences without parole for juveniles. But in Missouri, it was nine years later that a federal class action lawsuit made the possibility of release a reality for those incarcerated as youths.

In Miller v Alabama, the U.S Supreme Court recognized what science has long known: the brain of a youth is not yet fully developed, and these developmental differences counsel against sentencing a child to prison for life. Before meting out punishment, courts must consider the individual’s age and maturity, environmental circumstances, circumstances of the crime (including the child’s role, and the influence of peer pressure); how the incapacities of youth may have disadvantaged the individual in dealing with the legal system; and potential for rehabilitation. In short, juvenile cases differ from adult cases. These differences are equally relevant to parole decisions. However, Missouri was one state where the parole process continued to operate without regard towards juvenile offenders.

That’s what prompted the MacArthur Justice Center to file Brown v. Precythe in 2017, challenging the Missouri Parole Board’s treatment of its juvenile lifers. By 2018, a federal judge ruled that the state’s handling of JLWOP cases was indeed unconstitutional, a decision that was then upheld by the Eighth Circuit in September 2021. Unfortunately, this month, the court granted the State’s petition for rehearing en banc, meaning that the fight to defend Brown’s important victory will continue this coming January.

Since 2018, Brown v. Precythe has granted parole to 43 of the almost 100 statewide JLWOP individuals, who thought they would never see life beyond bars again. There are 53 parole hearings left for those who remain in prison, but only 16 of them have been scheduled in the coming years.

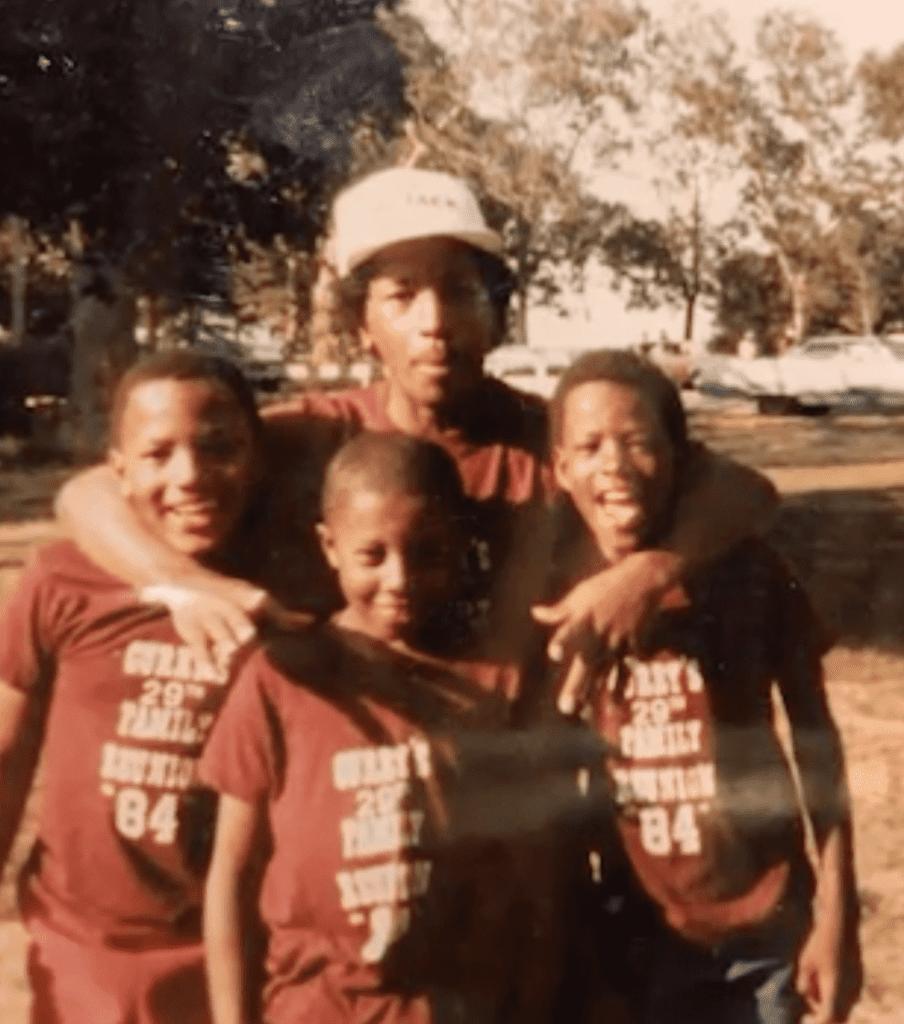

For Michael Vincent, who was released from prison in October 2020 after serving 30 years for a crime he committed at age 15, the decision gave him a new hope for freedom. “I never thought I was coming home, my family never thought I was coming home,” Vincent said. “This second chance at life, it’s a beautiful thing for me.”

But beyond the lives of JLWOP individuals, Brown v. Precythe has fundamentally changed how Miller cases are handled in the parole process.

After Miller, states that had sentenced kids to unconstitutional extreme sentences had to either resentence them or give them a realistic chance for release on parole. Missouri chose the latter. But the hearings were clearly stacked against impacted prisoners, largely shut out from their own parole hearings. The Parole Board allowed prisoners to have only a single “delegate” present, often forcing a choice between an attorney and a family member. That delegate was prohibited from taking notes or presenting evidence, inhibiting prisoners’ ability to present evidence of maturity and rehabilitation. The Board also prohibited prisoners or their attorneys from viewing the parole files that guide the hearings and decision. The Missouri Parole Board treated JLWOP individuals with arbitrary and cruel practices and then denied parole to over 85% of the people who had hearings and provided only boilerplate explanations for their decisions. In addition, the Board failed to consider the individual’s youth at the time of the crime, in direct contravention of Miller.

“Nothing in practice was changing for them,” said Renee Warden, a Juvenile Parole Fellow at the MacArthur Justice Center’s Missouri office. “They got a hearing, but nobody really understood, or was interested in, implementing Miller in a meaningful way.”

A judge agreed that the Missouri Department of Corrections practices were unconstitutional and the Court issued a sweeping order detailing 20 demands to the Missouri Parole Board for how to handle the process for individuals serving juvenile LWOP sentences. Prisoners are now granted the right to have full access to their parole files and bring witnesses, even expert witnesses, to their parole hearings, allowing them to directly address discrepancies in their cases. Prisoners are also given proper legal representation if desired, permitting attorneys to advocate in their pre-hearing interviews and during their parole hearings.

The Parole Board itself also changed how they approached cases. Instead of a single Board member presiding over a hearing, they will now take place before two-three Board members. In addition, risk assessment tools, used to determine parole eligibility, cannot be used unless they are specifically tailored to juvenile offenders because it may hold their youth at the time of the offense against them. The Court also targeted the discrimination of JLWOP prisoners, prohibiting any impediment in program participation based on JLWOP status. Most importantly, the Board is now required to document the evidence and reasoning used when making their parole decisions, forcing them to examine the environmental factors and youthfulness of the prisoner during the time of the offense, and is barred from making decisions based solely on the seriousness of the crime.

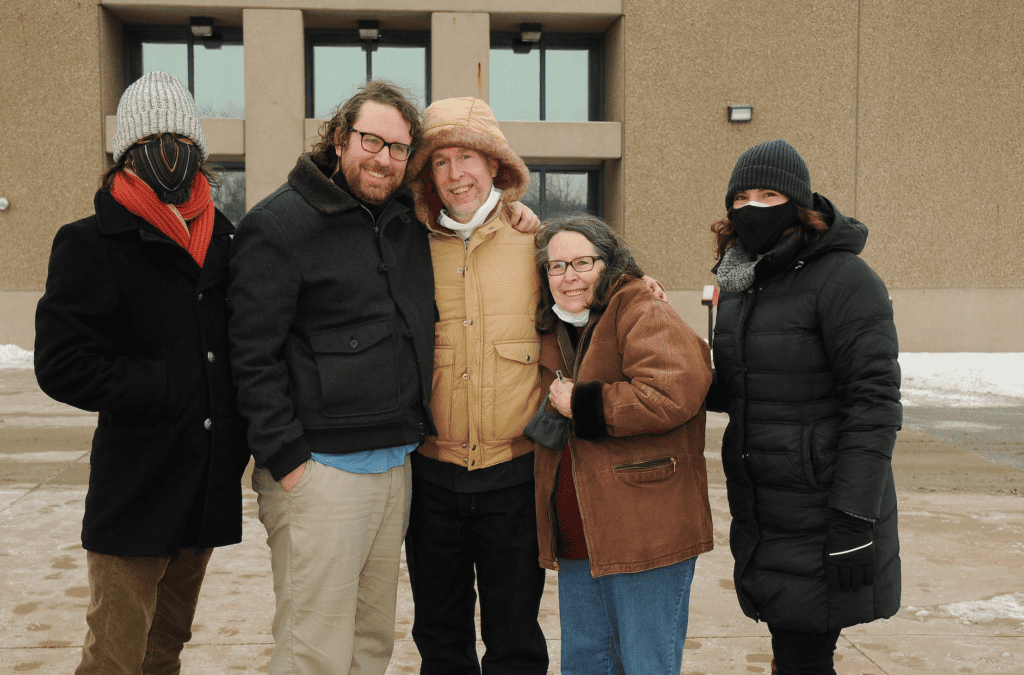

With these critical changes to the parole process, the stakes are clear as we fight to uphold the principles of Brown in court. Brown’s implementation means a fair chance for juveniles sentenced to LWOP – and a chance to show that the mistakes made in our youth doesn’t justify a lifetime of punishment. “We all make mistakes and you serve your time,” said Chris Polk, who was released in September 2020 after serving 26 years in prison. “And there’s so much growth and so much development that goes on in that process that I can’t even explain it.”

And while the fight in court continues, the success of Brown is clearly a sign of progress. In a conservative state like Missouri, Brown is indicative of changing public opinions nationwide regarding criminal justice. It’s especially promising for advocates looking to push back against extreme sentences and demand overdue parole reform for youthful offenders. “The law is catching up with social attitudes and science,” says Shubra Ohri, an attorney with MJC’s Missouri office. “If other courts come down with this similar decision, a lot more people are going to get a real chance to talk about how they’ve grown and that opportunity can equate to freedom.”

-

The Eighth Circuit

will again hear arguments on Brown in January 2022. -

The unique circumstances of JLWOP cases,

such as demonstrated maturity, must now be considered and explained in parole boards’ decisions. -

Youthful offenders can now tell their stories

to the parole board and play an active part in their parole proceedings. -

43 of almost 100

statewide JLWOP individuals who classify under Brown have been granted parole.