ShotSpotter is a Failure. What’s Next?

One year ago, the MacArthur Justice Center (MJC) published a study on the dangerous inaccuracy of ShotSpotter, a surveillance system that purports to detect the sounds and location of gunfire.

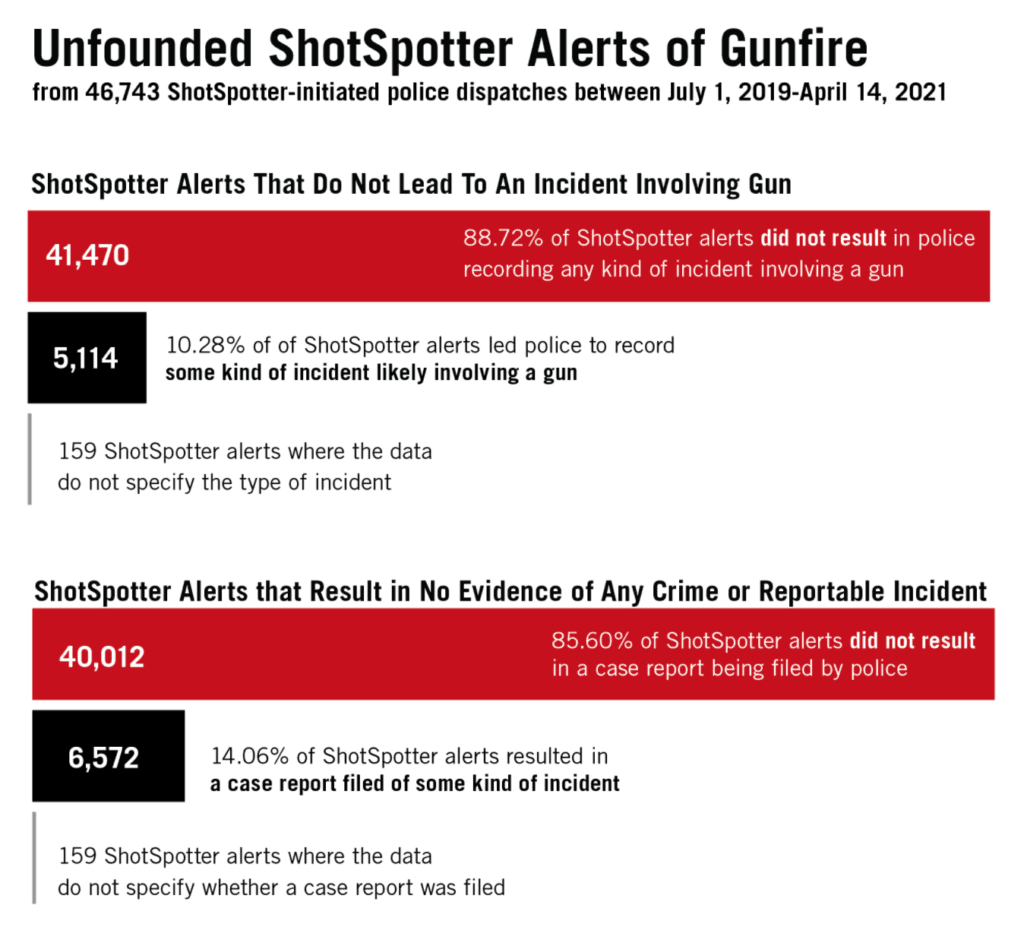

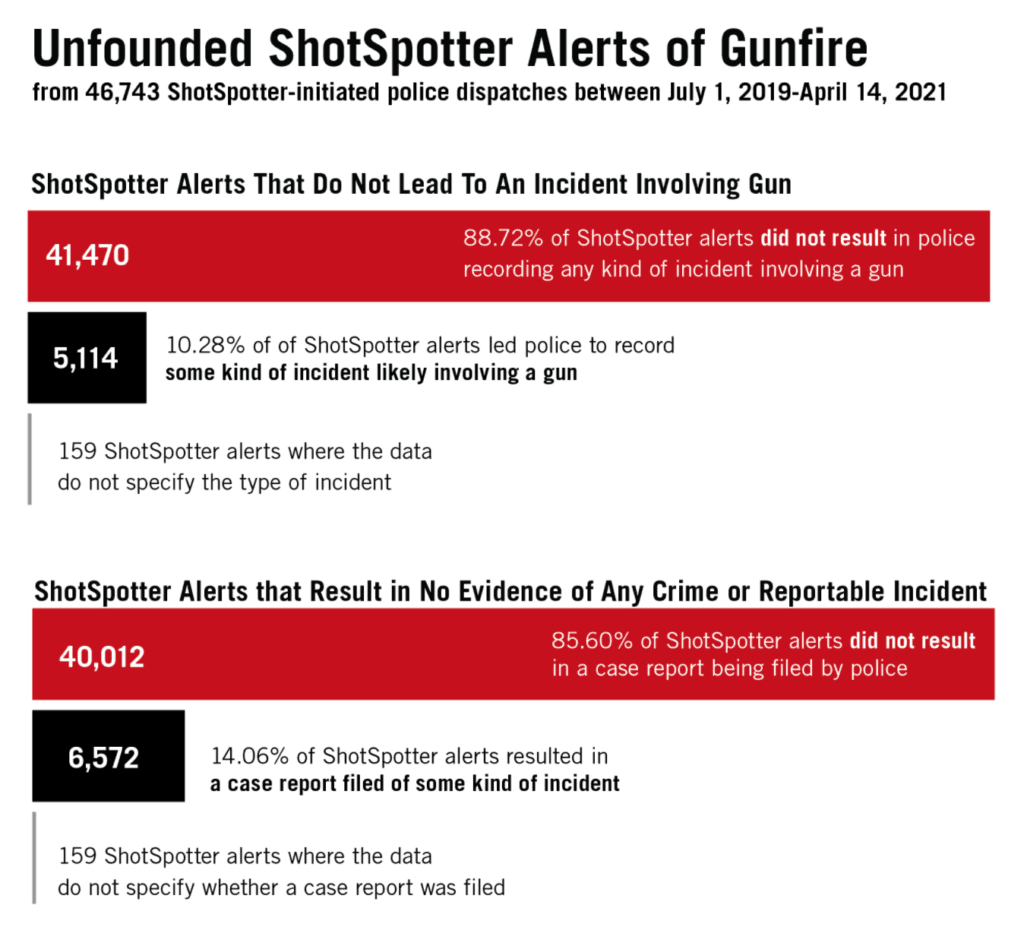

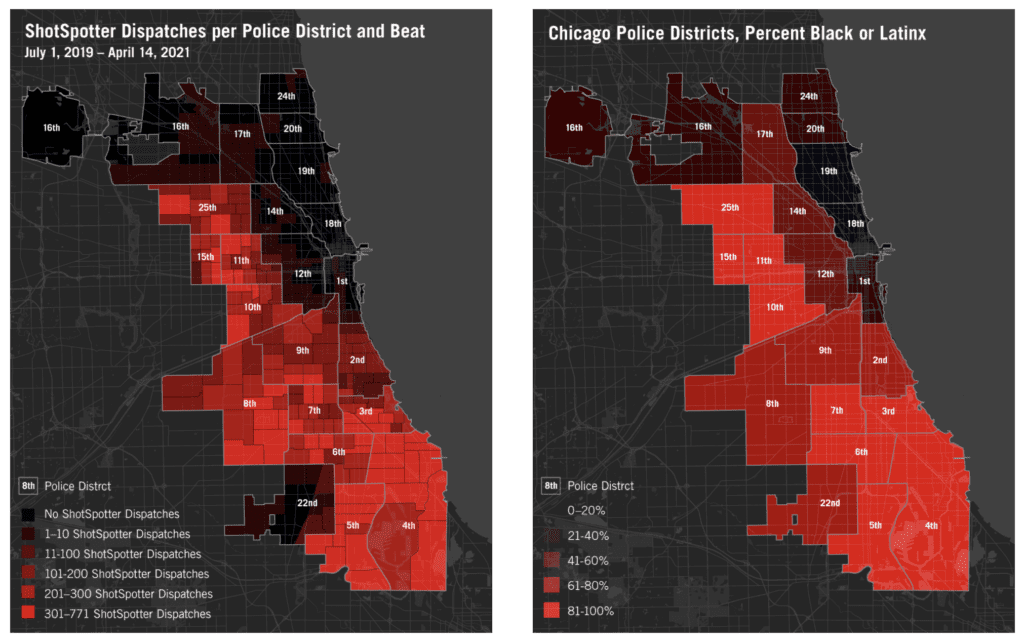

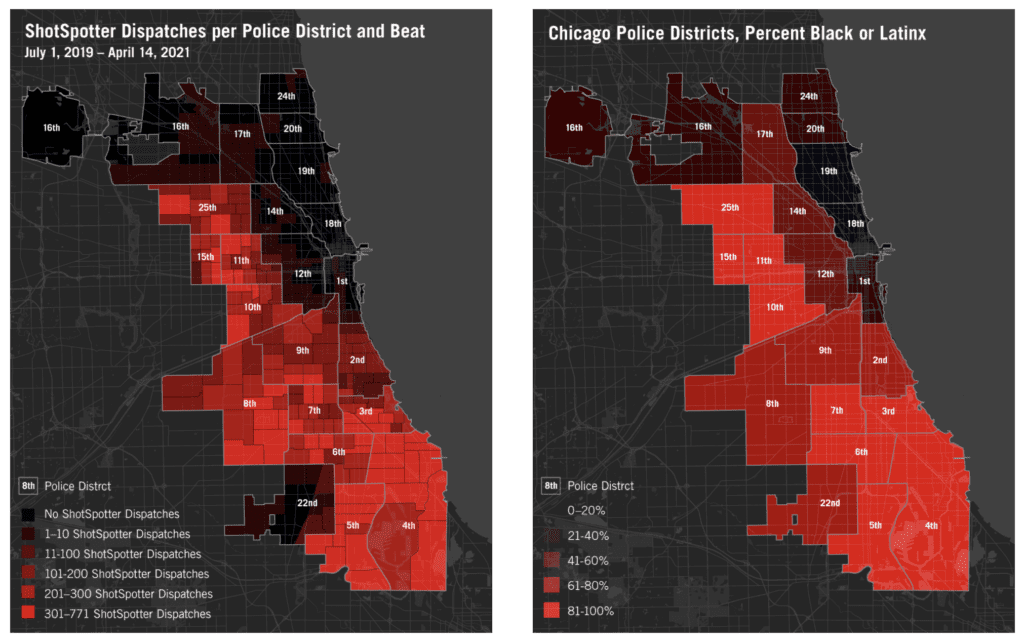

The study, which reviewed ShotSpotter deployments for roughly 21 months (from July 1, 2019, through April 14, 2021) using data obtained from the City of Chicago, found that 89% of ShotSpotter’s reports led police to find no gun-related crime and 86% turned up no crime at all, amounting to about 40,000 dead-end ShotSpotter deployments. Since then, a tool that was once merely a note in a crime report has become the subject of widespread scrutiny and concern by academics, researchers, and the media. Activists are increasingly calling for the removal of ShotSpotter from cities and police departments, pointing to the high number of pointless and potentially dangerous police deployments and ties to racialized police tactics.

ShotSpotter claims that its technology is able to identify gunfire by blanketing neighborhoods with microphone sensors. These sensors detect loud noises, and reports are sent to local police departments so officers can be deployed, in theory making police departments more accurate and efficient at responding to gun crime in their cities. The data analyzed by MJC told a different story.

“I remember running the numbers and thinking, surely I’ve got something wrong here,” MJC attorney Jonathan Manes, who leads the organization’s ShotSpotter efforts. “The sheer number of dead-end police deployments was jaw dropping.” Shortly after the release of the study, the City of Chicago’s Office of the Inspector General conducted its own analysis, which referenced and reinforced the MJC’s findings, saying “The [Chicago Police Department (CPD)] data examined by OIG does not support a conclusion that ShotSpotter is an effective tool in developing evidence of gun-related crime.”

Despite the MJC’s study findings, as well as the Inspector General’s confirmation of those findings, ShotSpotter continues to show clear disdain toward scientific testing and accountability, going so far as to fight in court to shield its methods of detection from public scrutiny, hiding even the basic guidelines its staff use to decide whether audio snippets ShotSpotter collects are actual gunfire. ShotSpotter, Inc. continues to claim a supposed 97% “accuracy” rate. To that end, they paid a consultant to “audit” this number. But the audit actually confirmed that this is not an accuracy rate at all, reflecting no actual testing of the system. Instead, it showed that ShotSpotter just assumes that all of its alerts are gunshots unless local police happen to file a complaint with the company reporting a potential error. ShotSpotter’s supposed “accuracy” claims are actually just a tally of customer complaints. And, according to Manes, CPD does not report any of the tens of thousands of dead-end alerts to ShotSpotter.

Not only are the CPD not reporting these apparent false alerts, but, as the Chicago OIG detailed, police regularly use the presence of ShotSpotter to justify intrusive and unwarranted police action, such as stop-and-frisk. OIG found more than 2,400 stop-and-frisks tied to ShotSpotter alerts, and only a tiny fraction of those led police to identify any crime.

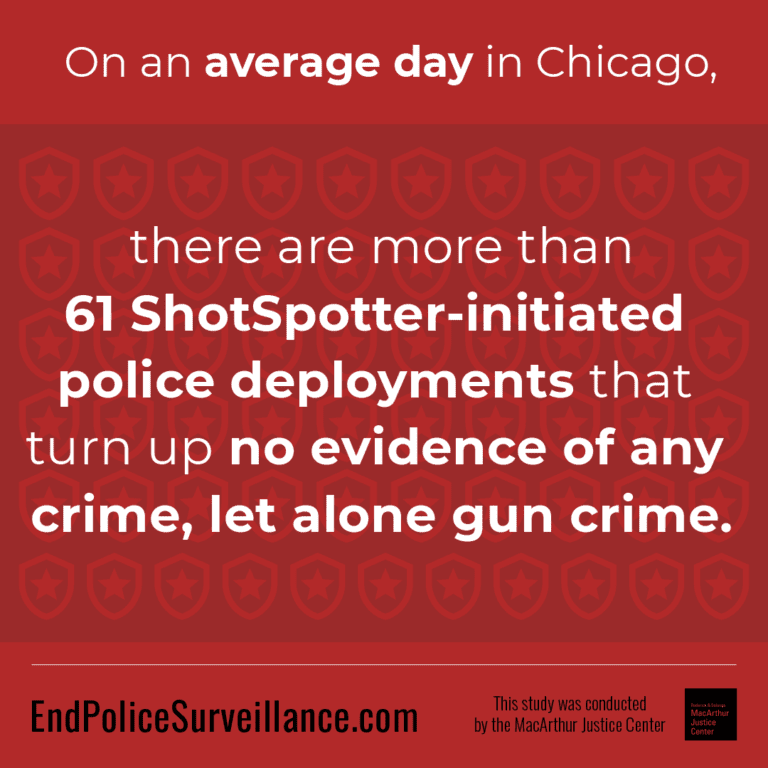

Every unfounded ShotSpotter deployment can lead to residents being stopped, detained and interrogated – often without them knowing why. This has a disproportionate impact on communities of color, particularly in Chicago where ShotSpotter technology has been exclusively deployed in the 12 districts with the highest proportion of Black and Latinx residents and the lowest proportion of white residents. On an average day, ShotSpotter sends police into these communities more than 61 times looking for gunfire in vain.

There have even been recent reports that ShotSpotter evidence leads to wrongful prosecutions, including that of Michael Williams of Chicago, who was falsely accused and jailed for nearly a year in 2021 largely on the basis of ShotSpotter evidence. When prosecutors eventually abandoned the ShotSpotter evidence they immediately dropped all charges. ShotSpotter, Inc. is also being sued, along with the City of Rochester, for malicious prosecution by a man who was acquitted of murder charges that were based on ShotSpotter reports.

In response to its technology being increasingly scrutinized in the media, including a BBC News investigative report that featured Williams, as well as a NBC News investigative report on the company’s usage of public relations and federal funding to win police department contracts, ShotSpotter, Inc. has launched a PR blitz and legal attack against outlets that have raised questions about their technology. One prominent example is a VICE Media series on the technology’s damaging effect on communities, which led to a $300 million defamation lawsuit against VICE Media from ShotSpotter.

Activists have demanded that cities and police drop ShotSpotter technology and redirect the millions of dollars it costs toward genuine, community-based violence prevention. In Chicago, members of the #StopShotSpotter Coalition have held rallies, teach-ins, briefings for elected officials, and protests against the renewal of the city’s contract with ShotSpotter, citing its inaccuracies, as well as concerns about police departments putting money into surveillance rather than investing in communities. Since the MJC study was released, organizing against ShotSpotter, Inc. and its technology has gained traction, including in cities such as Louisville, Houston and Miami. National organizations have also now come out against ShotSpotter technology, including the ACLU and Electronic Frontier Foundation.

In November 2021, Chicago’s Public Safety Committee held a public hearing focused on ShotSpotter. Manes was invited to testify, as was Deborah Witzburg of the Office of Inspector General and ShotSpotter’s CEO and senior leadership. Over almost four hours, city Alders peppered ShotSpotter with questions about its marketing claims and poor results, expressing skepticism that the system helps reduce gun violence.

“Over last year, we’ve been able to expose this technology as the failure that it is, and we’ve been able to shine a light on this particular company’s misleading marketing,” Manes said. “As we continue to investigate and learn more, my hope is that this work leads to action and accountability.”

Takeaways

-

88.72% of ShotSpotter alerts

didn’t result in police reporting an incident involving a gun. -

86% of reports

led to no crime at all. -

There were over 40,000 dead-end deployments

over 21.5 months. -

ShotSpotter is deployed

in the 12 Chicago districts with the highest percentage of Black and Latinx residents. -

2021 study of 68 large metropolitan counties that adopted ShotSpotter

over the course of 17 years—from 1999 to 2016—found that “implementing ShotSpotter technology has no significant impact on firearm-related homicides or arrest outcomes.” -

ShotSpotter is only 2.2 seconds faster

than a 911 call, according to a 2017 study. -

Chicago paid $33 million

for a three-year contract with ShotSpotter in 2018.